Recently one of my new students asked this very reasonable question. However the answer is not easy to state. It’s a bit like asking how long is a piece of string. Even if you put some ‘way points’ in the question such as ‘how long does it take to become average/good/excellent…’ you are still left with defining what average/good/excellent means, or deciding who should make that definition.

However I thought I’d put my engineers mind to it and see if I could shed some light with my own experience, thoughts and opinion. I am not aware of any hard facts or research on ‘tango expertise’, but if anyone knows of such data let me know.

Let’s first look at the main components of the tango dance (in no particular order of importance);

- Choreography – the walk, the classic figures, the ‘tango steps’ which would be recognisably tango to all tango dancers.

- Technique – the dissociation, maintaining your own axis, the timing, foot shaping etc. The components recognisable by most tango dancers above beginners level, even if those dancers have not yet mastered them.

- Musicality – stepping on the strong beat, decorating using the melody and so on. Again most dancers except new beginners would be aware of the possibilities of enhancing a dance with musicality, even if they were not yet adept.

To become expert at tango, we need to excel in all three of these areas at the very least.

There are also many other parameters which may influence how quickly we learn tango such as our own innate abilities, our teachers capabilities and so on, but lets stick to what is perhaps more easily judged for the ‘average’ new starter.

We then come onto defining levels of expertise. The words ‘beginner’, ‘improver’, ‘intermediate’, ‘advanced’, ‘professional’, ‘world champion’ etc. are used throughout the tango world to describe the level of a dancer, but what do they actually mean?

Well, apart from the obvious ones at the far ends of the spectrum (‘beginner’ and ‘world champion’) the others are a little more difficult to pin down.

Some tango schools classify by calendar duration. For example a beginner is someone who has danced less than 6 months, or an intermediate is someone dancing for a minimum of 2 years. In my experience this is a fairly blunt tool to define a persons actual capability. I’ve danced with people who ‘feel’ like they’ve been dancing a couple of years, to be told they’ve only been dancing 6 months (but taking 5 classes and attending a couple of milongas each week of those 6 months). Equally I’ve danced with people who ‘feel’ like they are beginners, to be told that they’ve been dancing tango ’10 years, on and off’. So the simple passage of calendar time is not necessarily a good measure of progress or capability.

There is a school of thought (and empirical research across many fields lends support) that to become an ‘expert’ in any subject takes 10 years of deliberate practice, i.e. taking classes, practising with specific purpose, and performing while taking feedback.

This “10 year rule” was first proposed based on research about the amount of deliberate practice it took for someone to become a chess master, but since then has been found to be fairly consistent across many subject areas. This translates into thousands of hours of effort expended for the sole purpose of mastering a craft or activity.

By age twenty the best violinists are estimated to have engaged in deliberate practice for at least 10,000 hours. Expert performers arrange their lives around a commitment to daily practice. For example, expert musicians have been found to engage in deliberate practice approximately four hours per day, seven days a week, 365 days a year.

This would imply that if you go to a 1hr tango class once a week and do no more, it will take you 200 years to become expert! Equally it implies that if you work in a job where you spend 30-40 hours a week doing the same thing week in week out, then you would become an expert in about 6 years.

This makes sense, and explains why some people seem ‘better’ or ‘worse’ than they ‘should be’. If you put in a greater number of hours, regularly and consistently, you are more likely to be perceived as ‘better’, compared to someone doing a few hours here and there with many long gaps in between.

Varying the type of subject performance is also critical to achievement. You can go to as many tango classes and practise sessions as you like, but you may still feel out of your depth during your first social dance simply because the safe learning environment is different from the performance environment.

You can’t really know how good you are at any point in your learning until you put yourself to the test. This applies both in class (where you might eagerly volunteer to be the teachers demonstrator instead of hiding at the back), as well as at a social dance where, as nervous as you may feel, you just have to get up and do it.

The trick to dealing with the inevitable mistakes in both class and milonga is simply to use the mistake as a learning tool, always looking for the useful learning points. In that way you make progress even when things feel uncomfortable.

So if you’ve read this far and are thinking you might never be any good at tango and you might as well give it up, take heart, because as yet I haven’t discussed another important parameter, which is your own objectives in learning tango.

What do you want out of tango?

Some people only want to do enough to be able to mug along at some occasional tangoesque type event. Some people want to challenge themselves to see how good they can become, and of course some people may dream of being a national or international champion. These objectives require different levels of committent and determination.

So in a nut-shell:-

1. Unless you intend to enter the World Championships or perform on stage, you don’t need to be ‘expert’ at tango to enjoy social dancing, but in order to get lots of dances you need to be acknowledged as ‘reasonably good’ within your tango community, so some time and effort is required. Maybe not 10,000 hours, but certainly many hundreds to the odd thousand or so hours.

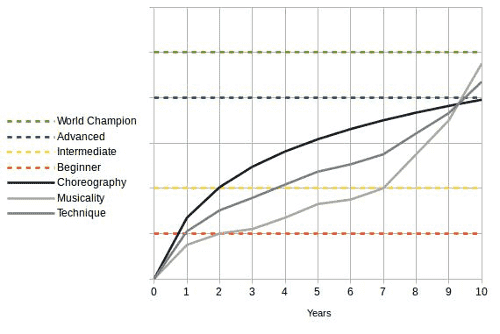

2. I believe that the act of learning the components of tango is something like the illustration below:

Before you all get up in arms about how ‘inaccurate’ this is, one should take it with a healthy dose of standard deviation, and your experience may well be different. This is based on my personal experience, what I observe of dancers around my community, and a smidgeon of thought and logical deduction. For example, why do the three parameters stop below the level of ‘World Champion’? Well, it’s my opinion that World Champions have some other harder to define ‘je ne se quoi’. It may be inspiration, or luck on the day, but it’s unlikely to be lack of technique, musicality or choreographic ability at that level.

So the chart shows that you may learn a fair bit of choreography reasonably quickly, but technique and musicality take longer. It also shows that the path to tango nirvana is never a straight smooth line. Sometimes you plateau and think you’ll never make further progress. That is the time to seek out input from someone much further along the curve.

3. If you want to compress the learning curve(s) then you need to do more work, more often and develop a commitment to deliberate practise each day, even if you can only manage 15 minutes instead of the 4 hours of experts. It should make a positive difference to your tango provided you’re practising how to become better, rather than just re-enforcing bad habits. In other words really listen to the advice your teachers give you, and practice the good stuff.

So how long does it take to learn tango? Well, first you need a find a piece of string… 🙂