In this series of articles about the important subject of musicality I will look at elements of music and some basic terminology (this article), followed by articles on Orchestra instruments, the structure of tango music, and then I’ll take a look at some famous Tango Orchestras and tunes and how the arrangers changed a tune to match their Orchestras sound. All the while I will be attempting to relate the information to interpretation of the music with your tango dancing.

You do not need to be able to read music to dance, but in order to hear the music and improve our musical interpretation of the Argentine Tango tunes we all love to dance to we must first understand a little bit about music and it’s components. I first present little music theory and terminology might be in order, so that when you attend musicality classes you begin to understand what tempo, rhythm, melody, music beat, etc. are all about and how they relate to tango and other music.

Music Terminology

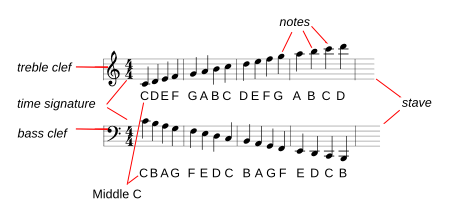

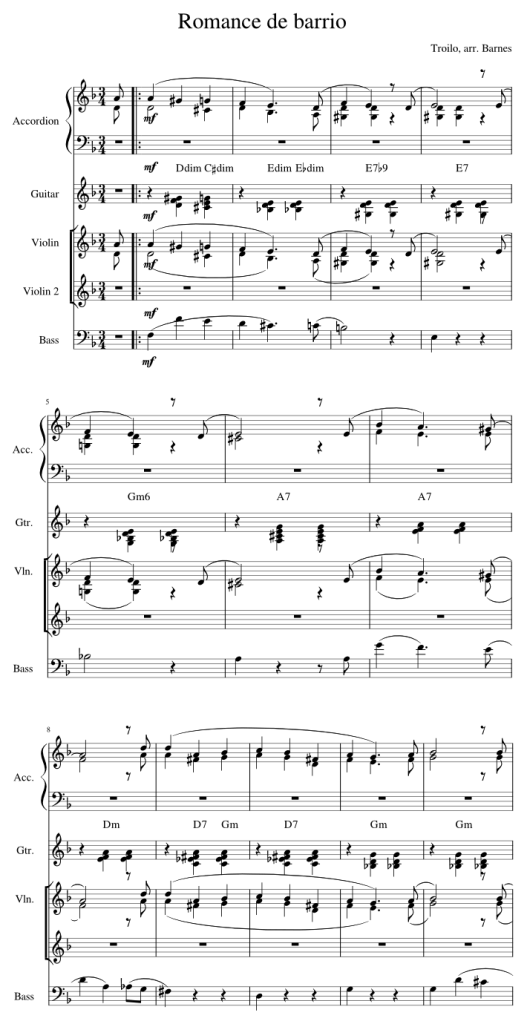

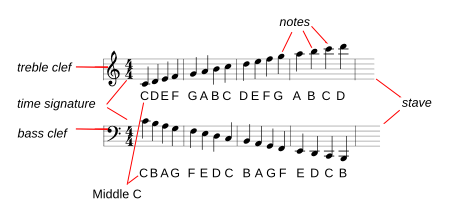

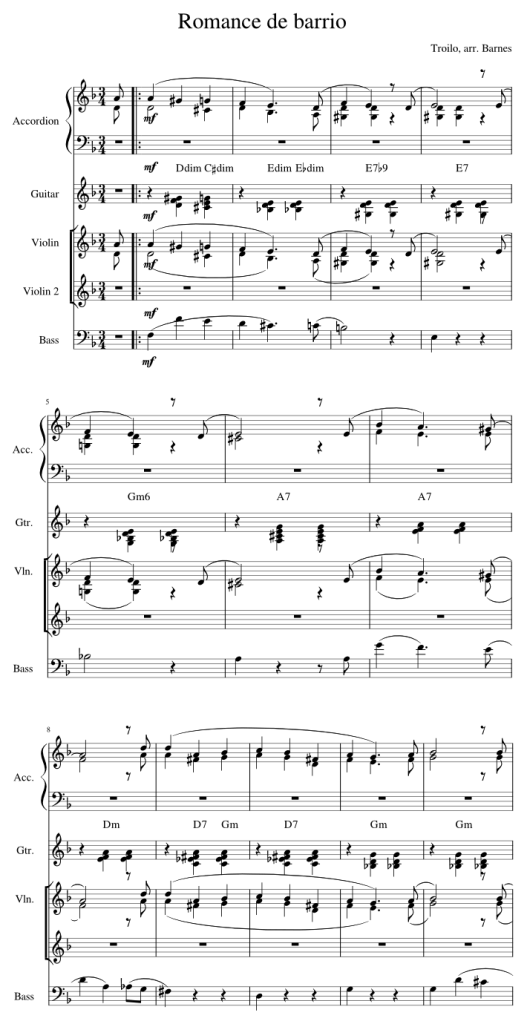

Written music is represented by a notation consisting of a series of horizontal lines (stave) upon which musical notes are represented in both pitch (where they are positioned on the stave) and duration (the particular symbol used to represent one note).

We can use two staves printed one above the other to represent the treble notes (high pitch) and bass notes (low pitch) and we use symbols (treble or bass clef) at the beginning of a stave to show which range the notes are in. So as notes are placed higher on the stave, they increase in pitch, and lower on the stave they decrease in pitch. You’ll also notice there is a repeating pattern where the note sequence starts again but at a higher pitch. This is called an octave. For example, when the middle C string on a piano is struck it vibrates at 261.6 Hz (Hertz or cycles per second), and the next C above vibrates at a frequency of 523.2 Hz. In other words for each octave a note will vibrate twice as fast for the octave higher, and half as fast for the octave lower. This is why, for example, all C notes sound similar but are a different pitch (frequency) to each other.

So as notes are placed higher on the stave, they increase in pitch, and lower on the stave they decrease in pitch. You’ll also notice there is a repeating pattern where the note sequence starts again but at a higher pitch. This is called an octave. For example, when the middle C string on a piano is struck it vibrates at 261.6 Hz (Hertz or cycles per second), and the next C above vibrates at a frequency of 523.2 Hz. In other words for each octave a note will vibrate twice as fast for the octave higher, and half as fast for the octave lower. This is why, for example, all C notes sound similar but are a different pitch (frequency) to each other.

We now know how to represent the pitch or frequency of a note, by it’s position of a treble or bass stave, but how about duration? The duration of a note is defined as a set of note symbols which represent relative duration to each other, and are as follows

One whole note (semibreve) = 2 half notes (minims), one minim = 2 quarter notes (crotchets), and so on. In terms of duration then, two minim notes and four crotchets take exactly the same duration to play, as do one semibreve and eight quavers. Note that it doesn’t matter whether the tails are pointing up or down. The usual convention is to keep the tail inside the related stave as much as possible

Hang on a minute (a minuet?) though! If note duration are played relative to each other, how do we know how fast to play the whole piece of music? This is entirely down to either the composer or the musician, but there are clues in the notation.

For example the composer could annotate a ‘metronome mark’ which indicates how many beats per minute the tempo should be. They look like this and are written just above the top stave on the left of the page.

This means ‘play at 120 beats per minute’. The note symbol is a crotchet so it also means ‘play at 120 crotchets per minute’. A metronome marks with a ‘c’ in front of the number mean ‘approximately’ (circa).

This means ‘play at 120 beats per minute’. The note symbol is a crotchet so it also means ‘play at 120 crotchets per minute’. A metronome marks with a ‘c’ in front of the number mean ‘approximately’ (circa).

Other ways of indicating the tempo may consist of a few words at the top of the page, often in Italian but not exclusively so.

Allegro (fast)

Adagio (slow)

Andante (at walking pace)

Allegro ma non troppo (fast but not too fast)

and so on. This form of notation is less specific and it’s left to the musician to decide what ‘fast’ or ‘slow’ means.

Time signatures

Previously we’ve considered the pitch of notes relative to each other, and relative to a treble or bass stave, the tempo of a piece, and a vague reference to how we can locate one of the notes (middle C) on a Piano (it’s in the middle of the keyboard 🙂 ) to anchor an entire piece of music into the correct set of octaves.

Now we can consider how to express an accented beat, which means placing an emphasis on one of a group of notes. We can do this with ‘bars’ and time signatures.

If you imagine a simple clock ticking, the regular tick represents the clocks rhythm or beat, but it has no accent. Each tick sounds exactly like the previous tick. Imagine now, if you had a clock ticking away, but on every fourth tick, the tick sounded louder, then the volume dropped back to normal for the next three ticks. This louder tick would represent an accentuated beat.

A time signature basically describes the underlying pattern of beats and the accentuation, so in our clock example, a time signature might describe the group of 4 ticks but with the first tick of each group of four being accentuated.

So in the following example of music you will notice that the notes are grouped into sections (or bars) indicated by the vertical lines on the stave. Each vertical line shows where the accentuated beat of the next bar occurs – the note immediately after the vertical line. The other squiggly bits and lines on the stave between notes represent rests (silence) of different durations, or marks representing expression. Silence or pauses, are also useful in interpreting your tango dance.

The other squiggly bits and lines on the stave between notes represent rests (silence) of different durations, or marks representing expression. Silence or pauses, are also useful in interpreting your tango dance.

Unfortunately we are still left with a choice of which duration of note (crotchets, minims, quavers etc.) should represent the beats in a bar, so we still don’t quite know exactly how long the duration of a bar should be… until we specify the time signature. Here are some examples used in tango music. The number on the bottom represents what note value each beat has. ‘2’ represents a minim per beat, ‘4’ represents a crotchet per beat, and ‘8’ represents a quaver per beat, so in the three examples above, the beat is represented by a crotchet. The top number then tells you how many beats there are in one bar, so

The number on the bottom represents what note value each beat has. ‘2’ represents a minim per beat, ‘4’ represents a crotchet per beat, and ‘8’ represents a quaver per beat, so in the three examples above, the beat is represented by a crotchet. The top number then tells you how many beats there are in one bar, so

- 4/4 says each beat is represented by the duration of a crotchet, and there are 4 beats (or crotchets) to a bar.

- 3/4 says each beat is represented by the duration of a crotchet, and there are 3 beats (or crotchets) to a bar. This is waltz timing.

- 2/4 says each beat is represented by the duration of a crotchet, and there are 2 beats (or crotchets) to a bar.

So is 3/4 time the same as 6/8 time? Well not quite, cos it’s not maths 🙂

If we go back to our ticking clock example with a 3/4 time signature, the clock tick would be

T t t T t t T t t with ‘T’ being the emphasised beat 1.

The 6/8 time signature would have a beat pattern of

T t t t t t T t t t t t T t t t t t

twice as many beats but each beat duration on half as long (a quaver not a crotchet), but the emphasised beat 1 is only half the duration as in 3/4 time. The rhythm sounds similar but not identical.

So why are some tangos written in 2/4 time instead of 4/4 time? Well rhythmically it wouldn’t make much difference to the dancer if they were stepping on both beats (in 2/4 time) or stepping on beat 1 & 3 (in 4/4 time) for their basic tango walk. Beat one would still be the emphasised beat, and using notes of different durations would still allow the composer to express melody and accompaniment in either time signature. It could be simply down to the composer to choose. For example, early tango pieces such as El Chocolo (A.G. Villoldo) were often written in 2/4 time whereas later works such as Libertango (Astor Piazolla) was written in 4/4 time. Libertango might be considered as more of a concert piece. Perhaps a ‘proper’ musician could tell us if there any advantages one way or another?

So what have we learned about music?

- It’s a bit complex, but then little kids can learn it by practising a lot, so no excuses… 🙂

- There are many elements of notation which can be used to express a tune onto paper. Some of the terminology is a little obscure to a non-Italian speaking non-musician, but once the notation has been learned it is possible to get into the structure, tempo, and musical expression in a tune, as performed by the musicians.

- For all the variety of notation elements for beats, notes, expression, silence etc., there is still a certain amount of interpretation by both the composer and the musician in what the notation exactly means. Musicians sometimes still have to hear a piece of music played before they can ‘read off the sheet’.

As a dancer it helps to be familiar with a particular tune in order to maximally interpret it, but as you will see in the following parts of this series, there is a structure to music and often a repetitious nature to elements of a tune. Once you’ve heard just one section of a tango tune, it is possible to anticipate what the tune will sound like later on, and therefore better interpret the music with your dance.

Although I have given a brief overview of the main aspects of written music, you do not need to be able to read music to dance to it. However in the next few posts when I look at how music can be interpreted in dance I will use this terminology, so refer back to this page if you need to.

Please note I am not a professional musician. Much of this material I’ve learned through study, my amateur attempts to play instruments (badly 🙂 ) and to write bits of music (equally badly, but one day… 🙂 ) and dancing to tango music (Hmmm… beginning to get there 🙂 ).

I used the first few chapters of the following book to write this little overview and can recommend it for any non-musician. The book is called called ‘Learning to Read Music by Peter Nickol’ if you want to delve into reading music in a more thorough way. Its a good introduction and pretty much tells you what you need to know to start reading music (and his explanations are a bit more thorough than mine).

In the next part of this series, I will examine the elements of a tune which a tango dancer could learn to interpret.

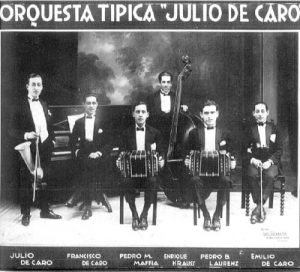

In the second part of this series we looked at which elements of a tango tune could be expressed in your dance, and in order to look at those elements in more detail we need to first have a quick look at the orchestra, the instruments and how they express different elements of the music before looking at tango tunes in detail.

In the second part of this series we looked at which elements of a tango tune could be expressed in your dance, and in order to look at those elements in more detail we need to first have a quick look at the orchestra, the instruments and how they express different elements of the music before looking at tango tunes in detail.